More than half a dozen books and documentaries tell the stories of Washington, D.C.’s punk music scene—one that birthed famous musicians, created noteworthy clubs and venues, and continues to inspire bands and social activists today. People who know anything about punk know groups who emerged from D.C., including the likes of Fugazi, Bad Brains, Minor Threat, and Bikini Kill.

Often forgotten and ignored—although just forty-five minutes away—Baltimore had a punk scene, too. But finding anything that tells the story of it today is nearly impossible. That is, unless you’ve been to Celebrated Summer Records in Hampden, where owner Tony Pence has created a mini museum of punk fliers, photos, t-shirts, posters, and setlists that he’s collected throughout the years.

While his items highlight many bands, scenes, and genres that interest him outside of his native Baltimore, he has perhaps one of the best collections documenting the local punk scene.

This August, Pence is compiling hundreds of his keepsakes in a show of “raw and rare ephemera” at Metro Gallery, featuring Baltimore’s lesser known punk underground from 1977 to 1989.

“Baltimore had a scene too,” Pence says. “People forget that this happened here.” He adds that he wants to celebrate Baltimore musicians and venues that hosted more famous bands on tour, like the Circle Jerks, Dead Kennedys, and Black Flag.

To show that this era still inspires, the exhibit will open with a reception and live performances on August 3rd. Coinciding with Celebrated Summer’s 13th anniversary, the event will feature bands that capture the general style of 1980s punk, including Philadelphia-based Dark Thoughts, Pence’s band Glue Traps, and Ammo from New Jersey.

“It’s going be an interesting glimpse into the subculture of this city that doesn’t really get a light shone on it very much,” says Metro Gallery manager Patrick Martin.

The exhibit itself ends up being as close to a time machine as Pence can offer. Hundreds of artifacts create an immersive experience of what it would have been like at iconic spaces such as the Marble Bar, Godfrey’s Ballroom, and Eutaw Clubhouse in the late 1970s and 1980s. As much as possible, Pence has organized the material chronologically and by specific shows.

Photographs taken by documentary filmmaker Skizz Cyzyk—who was then just a punk kid playing in bands—put you in the room. Contemporaneous reviews in fan zines comment on shows, while Maximum Rock n’ Roll provides Baltimore “scene reports.”

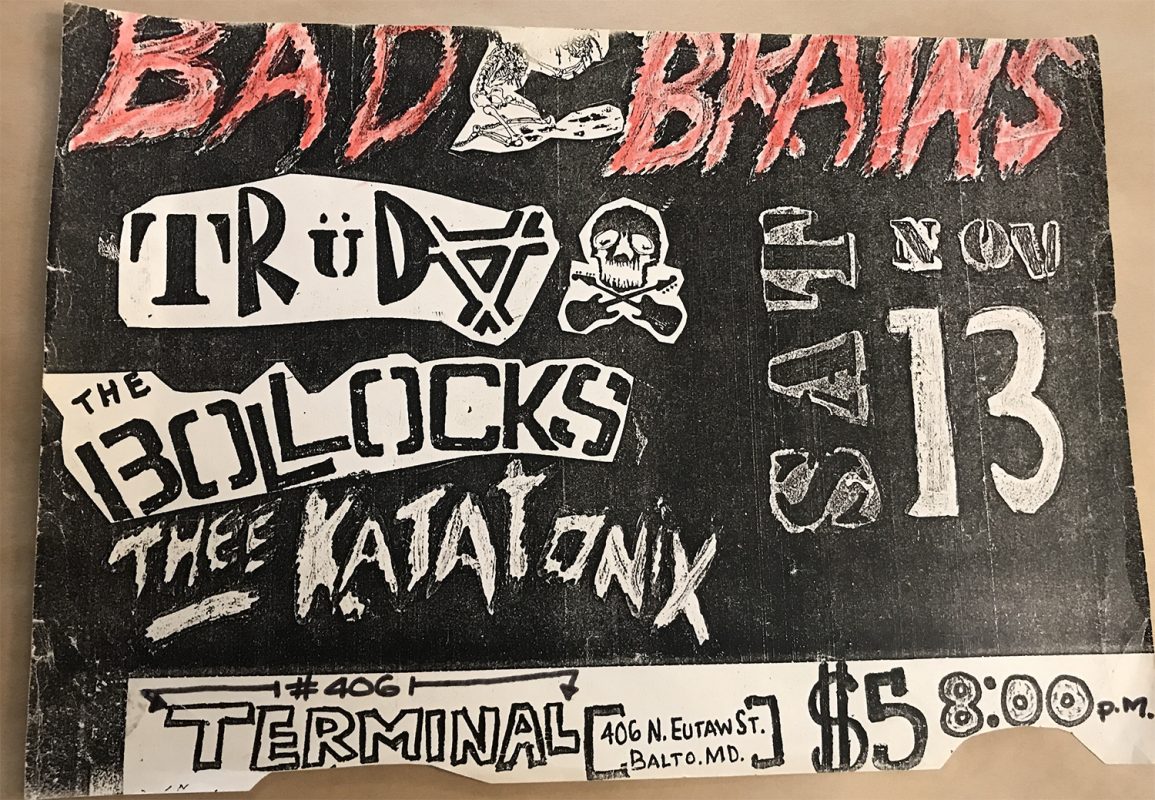

On a mixtape, you can listen to demos and songs off of rare albums. At least 150 fliers plaster the walls, like they would have plastered the streets of Baltimore, consisting of both original Xeroxed handouts and artwork cut out and taped together.

Almost every one includes an out-of-town and Baltimore band on the bill, and while local bands like Reptile House and Lungfish ended up being more well-known, Pence admits that many of the hometown names were “born and dead before anyone knew them.” He also has band t-shirts, setlists, tickets, the actual albums, and even a contract from when Black Flag played at Jules Loft on display.

He gave the show the name “Killed by Charm,” a reference to bootleg punk compilations from the late 1980s featuring the obscure and forgotten—one of which included Baltimore band Ebenezer and the Bludgeons. The earliest flier Pence has on display is from when the band played at the Oddfellows Hall in Towson in 1977.

“I didn’t go to these original shows,” Pence says, explaining that he wasn’t old enough and was more into metal as a teenager. “This isn’t supposed to be definitive.” He adds that he hopes this show will help other punk enthusiasts come out of the woodwork to share their experiences. “There are people out there with more knowledge.”

Although he loves the ephemera, he doesn’t hang it just to show off. Instead, he wants to highlight the DIY ethos of punk—something he hopes the Killed by Charm show highlights.

During that era, punk was underground. Fliers were handmade, the albums were self-released or on small labels, and the were venues small. He says his true desire is for kids to see and hear all of this, and then think, “I can start a band. I can make a flier.” Then, he says, the punk tradition passes forward.